“Why read books?” A question which only decades ago would have been asked facetiously if at all has become increasingly relevant and serious in our digital age. Studies show that young people are giving up reading books in greater numbers, while becoming increasingly devoted to screen time as a replacement for reading time. It seems obvious that screens are the future. So why bother with books? What is to be gained in spending extended periods of time absorbing content from words on a non-interactive page? Quite a lot, as it turns out – and not just that content for its own sake, though the value of such content is not negligible. Reading develops not just the intellect, but also the emotions, the moral sense, and ultimately the spiritual imagination. As human beings created in the image of a verbal God who expresses himself to us through words on a page – and as creative beings whose imaginative capabilities reflect those of our creator – reading is a way of embracing who God made us to be. Reading may not make us human, but it certainly has the capacity to make us better people.

Even those who would deny the relevance of reading in our modern era would probably concede that non-fiction books can still be valuable as a source of information. Sit down for an extended session with a book of history, social science, or theology, and in due time the reader will undeniably gain information about the world he lives in. Indeed, for the serious student, reading as an information-gathering skill is essential. But why is reading a more valuable means of learning than, say, watching a documentary? While it is true that film can be a useful medium for learning, a book requires the reader to engage his rationality more fully. Unlike primarily visual media, text is propositional and logically progressive, and therefore, as Postman says, “the process [of reading] encourages rationality” (Postman 51). It also encourages mental engagement and active, rational response to the content – skills which are trained through reading text and which atrophy without it, as Bauerlein observes: “As [people] read linear texts in a linear fashion less and less, the less they engage in sustained linear thinking” (Bauerlein 141). In requiring the reader to engage logically and linearly with the content it presents, printed text encourages growth in the skill of linear thinking – a skill that is obviously essential for developing reasoned opinions, engaging with unfamiliar ideas, and expressing oneself persuasively to others. As Carr puts it, “The reading of a sequence of printed pages was valuable not just for the knowledge readers acquired from the author’s words but for the way those words set off intellectual vibrations within their own minds…people made their own associations, drew their own inferences and analogies, fostered their own ideas (Carr 64-65). The very act of absorbing content through reading develops the reader’s intellect in a way that other means of learning do not.

But reading is not simply a means of accumulating information – even information presented propositionally and in an organized manner – or training the intellect. Indeed, the reading of fiction – though probably a practice even more sidelined in today’s world – is a valuable and indeed irreplaceable component in the development of moral virtue. The reading of fiction offers distinct and invaluable opportunities for moral development to the student of virtue, providing a unique means for growth in character.

In today’s digital era, many studies have shown, “wired” individuals are increasingly and ironically disconnected from one another. Whether it’s the overwhelming over-sharing on Facebook or the egotistic self-absorption of the selfie era, it seems that those who are superficially most connected are actually losing their ability to empathize with the experiences of others. As Nicholas Carr puts it when summarizing a recent experiment demonstrating this, “The more distracted we become, the less able we are to experience the subtlest, most distinctively human forms of empathy [and] compassion” (Carr 221). In this environment, the reading of fiction as component of character development actually becomes even more significant. For the fiction reader, a 400-page novel is an opportunity to spend hours inside the mind and experience of another person: a fictional person, sure, but a character with thoughts, emotions, and experiences compellingly portrayed – and utterly separate from the reader’s own. In the experience of reading fiction and engaging imaginatively with the experience of another (fictional) person, the reader is practicing the skills which will enable him to empathize more fully with other human beings in real-life scenarios. Far from isolating himself through fiction, he is actually learning to rejoice with those who rejoice and weep with those who weep. Reading fiction truly teaches empathy.

In more general terms, reading fiction by definition exercises the imagination. Creating in one’s mind exciting action scenes, complex characters, and powerful moral dilemmas sourced from black ink on white paper clearly requires a robust imaginative effort. Like any other human faculty, the imagination must be developed and strengthened through use – and reading, especially reading fiction, provides opportunity for that use. In using our imaginations as we read, we embrace the God-given uniqueness of our humanity. Certainly human beings are the only creatures with the ability to imagine. One could even argue that our imagination is a significant factor in the image of God which He infused into us human beings. After all, the first we see of God in the Bible, He is creating the universe out of nothing – certainly an act of immense imagination if there ever was one. Perhaps by practicing imagination, we are honoring and reflecting the image of God in our human nature.

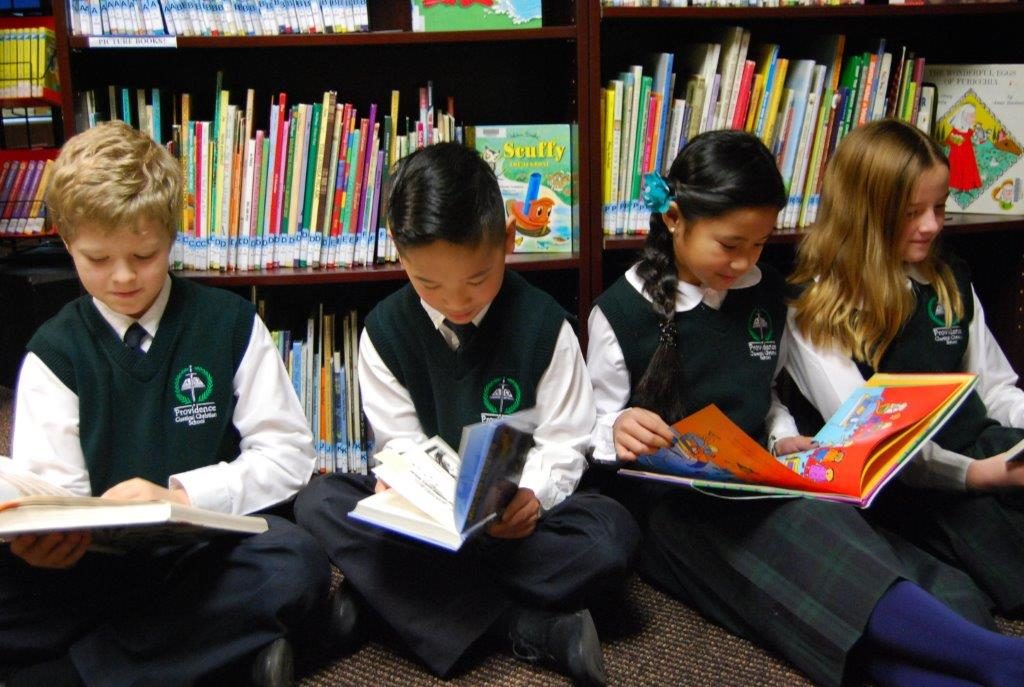

More specifically, the use of imagination required in reading fiction helps us develop into wise and virtuous human beings. For younger children in particular, we see this value as, through the imaginative reading of fiction, they develop a vision of attractive nobility as they read about characters growing into heroism. Vice versa, young children can also learn much through fiction about what they don’t want to emulate through reading about despicable, unjust characters and cheering for their downfall. The beauty of justice, the inspiring nature of hope, the attractiveness of virtue – all of these take fire in the imaginations of young readers of fiction, stirring and strengthening their moral imagination in ways more powerful and impactful than any lecture could do. I have many times had fourth graders tell me that the characters in a novel we’d read showed them how they wanted to be (or not be).

Fiction also allows the reader to learn moral lessons without the painful pitfalls of trial and error or the at times overwhelmingly high stakes of real-life scenarios. After watching a particular character make an egregiously bad choice in a novel – and suffer the natural consequences of his folly – even young children can learn much. They don’t need to try that particular poor choice for themselves to know it will not end well! For older readers, fiction allows them to engage with complex moral questions in a safe environment. Having already engaged with a complicated and challenging issue such as racial injustice, mental illness, or nihilism through the lens of a well-crafted, thought-filled fictional treatment, the reader will be better equipped later on to understand and face the challenges of real-life scenarios in which these issues arise. Even books which portray a questionable or downright false worldview are valuable in this way – they allow the maturing reader to wrestle with that perspective, come to understand it, and think through his response to it in an entirely safe and non-confrontational environment before he runs up against it in the real world.

Mysteriously yet significantly, the regular use and strengthening of the imagination also has important ramifications in the spiritual life of the reader. After all, to be a Christian, one must use one’s imagination. God is ever- and omni-present. He is both utterly One and also gloriously Three. He orders all things for His purposes, down the most minute detail slipping your notice at this very moment. This bread is a means of His grace to you. Your body will rise again at the end of time. All the most profound and beautiful truths of the Christian faith require the use of imagination. Those who have practiced imagining, who have strengthened their imaginative faculty through the regular reading of fiction, are better equipped to accept and love these truths. Perhaps this is a part of why God has given us the gift of imagination – and of reading – in the first place.

In the end: in the beginning was the Word. Language and the Word – both spoken and written – are an essential part of the divine nature, as well as of our human nature as God designed us, and also an essential part of how He reveals Himself to us. Central to this revelation is God’s Word, the Bible. A person who does not comfortably and regularly read books is unlikely to read the Bible comfortably and regularly either, and a Christian who does not read the Bible is handicapped in his ability to know and follow God. Reading is, therefore, of central importance for the Christian. Not only does it help us to learn, grow in empathy, and develop wisdom and even faith, but it also allows us to hear directly from God. Reading is and remains an essential pursuit, one for which we must fight against the cultural tides of our day.

TeacherBooks read and cited:

Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman

The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to our Brains by Nicholas Carr

The Dumbest Generation by Mark Bauerlein