December 6th was the commemoration of St. Nicholas of Myra, who died on that day in 342 AD. This ancient Greek Christian bishop from Asia Minor is one of the main inspirations behind the modern Santa Claus myth.

A Santa Claus with Hair on His Chest

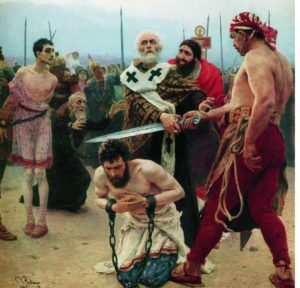

The above painting is based on a famous legend about the saint, depicting him not so much jolly as fiercely concerned for justice, grasping the executioner’s sword at the risk of his own life.

There are also many stories about Nicholas’ secretive gift-giving. One legend has Nicholas leaving coins in the shoes of the poor who left them out for him. In another legend, Nicholas hears of a poor man with three daughters. Since he is poor, he can’t afford a dowry for any of his daughters, and as such they would likely go unmarried and be forced to turn to a life of prostitution just to feed themselves. Nicholas secretly tosses three bags of money-one for each daughter-through a window, or in some versions, down the chimey. In one later version of the story, one of the daughters is drying her recently-washed stockings by the hearth, and a bag of gold is caught in one of them.

Historically, Nicholas was one of the bishops who answered Constantine’s call to iron out the details of the early Christian faith, being present at the resulting First Council of Nicaea, valiantly opposing the Arian heresy and defending the Orthodox doctrine of Christ, and signing the Nicene Creed.

The Long Road to Becoming Santa

Over the centuries, the stories of Nicholas’ life became mythologized, and he became known as the patron saint of children, sailors, archers, merchants, thieves, and even pawnbrokers.

As Europe became Christianized, Nicholas’ legends may have blended with the Nordic legends of Odin- another old, bearded winter gift-giver who additionally rode through the night sky on a gray 8-legged steed during Yule (yes, that’s where the term comes from).

Other figures were also thrown in to the mix, like England’s “Father Christmas.” Dating back as far as the reign of Henry VIII in the 16th century, Father Christmas was pictured as a large man in green or scarlet robes lined with fur (think The Ghost of Christmas Present in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol). Father Christmas typified the spirit of good cheer, bringing peace, joy, good food & wine, and revelry.

The tradition of the Christkindl, or Christ Child, also began in the 16th century, thanks largely to Martin Luther. For Protestants during the reformation, feast days for the saints (like Nicholas) were discouraged. Instead, the gift-giver was portrayed as a young child with blonde hair and angel’s wings, perhaps intended to remind people of the infant Jesus. This tradition is the origin of the name Kris Kringle.

In the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, Saint Nicholas became known as Sinterklaas (from Sint Nicolaas). Some of Nicholas’ remains were taken to an ancient city in Spain, so the Dutch legend has it that Sinterklaas travels from Spain (not the North Pole…) and arrives by steamboat (not reindeer- patron saint of sailors, remember?) with Zwarte Piet, or “Black Pete,” a helper who goes down the chimney for him and thus had a face backened by the soot.

All of these various figures became enmeshed together as Brittish, Dutch, and other European settlers came to colonial America. “Sinterklaas” was Americanized into “Santa Claus.” Throughout the nineteenth century, Christmas literature (such as The Night Before Christmas) and popular art (cf. Thomas Nast) exchanged Spain for the North Pole, a steamboat or 8-legged horse for a sleigh drawn by reindeer, and black-faced chimney-crawlers for hordes of toy-making elves, giving us the image we’re familiar with today.

To come full circle: in the Scandanavian countries that had originally provided the Odin legends, a being from Nordic folklore called Tomte or Nisse (portrayed as a short, bearded man dressed in gray clothes and a red hat) started to deliver the Christmas presents during the 1840s, inspired by Santa Claus traditions that were by that time spreading to Scandinavia. By the end of the 19th century this tradition had also spread to Norway and Sweden, replacing the Yule Goat (yes, a holiday goat- odd, but stranger still is the goat’s connection with another Norse god, one you’ve probably seen in a recent movie- Thor).

And After All That…Jesus.

At Annapolis, we firmly assert that the central figure of Christmas, of history, of the entire cosmos is simply Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ.

While there’s much to be said for the examples and heroes of church history, for the importance of family, for the virtues of hospitality and generosity, and for the satisfaction of researching and learning- any good that comes from any of these things is ultimately a good gift from the ultimate gift-giver. Nicholas would tell you himself if he could; by every account he loved Jesus.

Perhaps my favorite version of Santa Claus is C.S. Lewis’ “Father Christmas” in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Mr. Beaver and Peter, Susan, and Lucy are running from what they think is the White Witch’s sleigh. She’s captured their brother Edmund and locked the land of Narnia in an eternal winter- “always winter and never Christmas.” Hiding in a small hollow, they’re scared, desperate, and all but cornered by the sleigh until Mr. Beaver bravely peeks out.

“Come and see! This is a nasty knock for the Witch! It looks as if her power is already crumbling,” he says. The three children, confused, come out of hiding. They were fearing the Witch, but now they’re confronted with a large, bearded man in a red robe. They know him from earth as being funny and jolly, but now, face-to-face with him, something’s different. He’s so big, so glad, and so real, that they all became still and solemn, but also glad at seeing him.

He gives the children gifts- not cheap plastic or elf-made gadgets, but weapons to fight evil and injustice and tools to help and heal. Readers, and I get the feeling that even Peter, Susan, and Lucy, are all the while silently asking themselves: “What is he doing here? This is Narnia.” There’s a sort of expectation that Santa and Aslan are mutually incompatible.

Then Father Christmas tips his cards: “I’ve come at last. She has kept me out for a long time, but I have got in at last. Aslan is on the move.”

Aslan is on the move. With that one subversive phrase, Father Christmas shows that he himself is simply a fellow revolutionary, hopefully expecting Aslan’s return like the animals and the children. He shows that he is not Aslan’s competitor, but his loyal servant, like the real Nicholas and Jesus.

Whatever is true, noble, right, pure, lovely, admirable, excellent, or praiseworthy in the history and legend of Santa Claus (and to be sure, there’s much that isn’t), it only serves to point towards Jesus.

This holiday season, and all seasons, remember:

Jesus is on the move and He is the reason for the season.

Merry Christmas from all of us here at Providence!

Written by Peter Hansen, Annapolis Christian Academy Headmaster